In which I find myself surprisingly beguiled by Charles Dudley Warner.

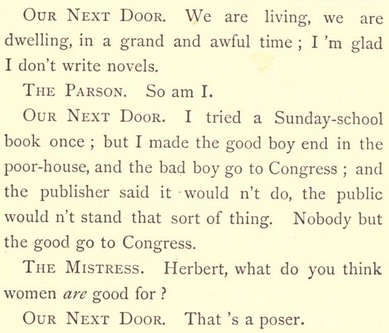

As I mentioned the other day, I don't know enough about Charles Dudley Warner. Indeed, and this is probably true of most, I only really know him as Mark Twain's neighbour in Nook Farm, Hartford; as co-author of The Gilded Age; and, as it goes, for his 1885 observations of the South, particularly New Orleans. I also knew one snippet of his 1873 essay collection, Backlog Studies - the famous bit, where a thinly disguised Mark Twain ("Our Next Door") chips into a conversation about literature in the post-war moment - an example of the chatter that was supposed to have given birth to The Gilded Age:

But Backlog Studies is far richer than this moment suggests. On the one hand, as the snippet above indicates, it does provide a fascinating snapshot of the heart of life in Nook Farm at its zenith - home, of course, not just to Warner and Twain but also Harriet Beecher Stowe and other assorted members of the Beecher mafia, and the site of frequent visits from the likes of William Dean Howells and Thomas Bailey Aldrich. In much of the book, Warner simply records the flow of conversation around his fireplace as it unfolded across one winter. As such, Backlog Studies does much to imagine Nook Farm as a place apparently marked out by its realisation of an idealized sense of community (something which the Henry Ward Beecher scandal would shake, if not destroy). As Justin Kaplan described it, speaking particularly of Twain's relationship to his Hartford neighbours:

On the other hand, however, Backlog Studies is also a text that feels connected to the kind of masculine, sentimental domesticity that I apparently can't get enough of at the moment. As a collection of essays, it certainly bears the influence of Charles Lamb (named in the text) and Oliver Wendell Holmes. But it also feels tonally related to, say, John Greenleaf Whittier's beautiful Snow-Bound (1866) or Ik Marvel's (really David Grant Mitchell's) earlier Reveries of a Bachelor (1850), and not least because of the shared centrality of the hearth and home in those texts. In the sections of the book where Warner philosophises at length about life and literature, using his fireplace as an organising principle, he conjures a completely compelling picture of postbellum domesticity in Nook Farm, tinged by nostalgia for life before the war ("It has been such a busy world for twenty years. So many things have been torn up by the roots"). The moment below seems to crystallise the kind of homely, sentimental pleasures that the text offers:

Well, has it? I'll return to Backlog Studies at some point, probably around Christmas - which seems fitting, right?